Day 2

Today will feature an introduction documentary editing and the the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI). There will also be a demonstration of documentary editing with Senate House Library manuscripts.

Aims

- Understand the difference between documentary editing and other forms of editing.

- General grasp of the Text Encoding Initiative and TEI schemas.

- Understanding of modelling texts.

Schedule: Day 2 (Tuesday, 3 July)

| Time | Topic | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 9.30 | Seminar 3: Documentary Editing | Presentation, Discussion |

| 11.30 | Seminar 4: Introduction to the Text Encoding Initiative; Text modelling | Presentation, discussion |

| 14.00 | Seminar 5: Letters and journals manuscripts (Senate House Library) | Digital lab |

| 16.00 | Library Time | Presentation |

Seminar 3: Documentary Editing

Readings

- G. Thomas Tanselle, “The Editing of Historical Documents.”

- Lou Burnard’s What is the TEI?

- James Cummings, “The Text Encoding Initiative and the Study of Literature”

- Elena Pierazzo, Digital Scholarly Editing (Chapter 2).

Documentary Editing

Lecture Notes

To make a long article short: transcribe as much as possible in a documentary edition.

The old divide between literary and historical editing. Historical: more about annotation (contextual commentary). Literary: more about textual variants.

Naive view: literary editing produces eclectic texts, historical editors produce "faithful" texts.

Literalness and exactness and critical. Faithfulness?

Modernisation and regularisation. What is lost by the editor imposing regularity and spelling changes on a historical or private document.

Jefferson "wd hve retird immedly hd h. nt bn infmd". What is lost by expanding the abbreviations?

Felicity to the document or to the reader?

Diplomatic: "wd hve retird immedly hd h. nt bn infmd";

Semi-diplomatic: "w[oul]d h[a]ve retir[e]d immed[iate]ly h[a]d h[e] n[o]t b[ee]n inf[or]m[e]d";

Clear text: would have retired immediately had he not been informed.

Yet: one cannot transcribe everything. As soon as transcription happens, an element of contingency comes into the text. It is still a representation.

Example 1: Mark Twain’s notebooks and journals. Access slides here.

Example 2: Christopher Cranch’s 1839 travel journal

Seminar 4: Brief Introduction to the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI)

Access the TEI intro slides here.

Text Modelling

“[E]very electronic representation of text is an interpretation” (Paul Eggert, Securing the Past, Cambridge UP, 2009).

And an argument, many say. Are these points obvious, or absurd?

Modelling: Our notions of modelling a text are really inherent in textual editing activities, but the theorising about modeling could point back to Willard McCarty’s insistence on the centrality of modelling in digital humanities projects (see his Humanities Computing, Palgrave, 2005).

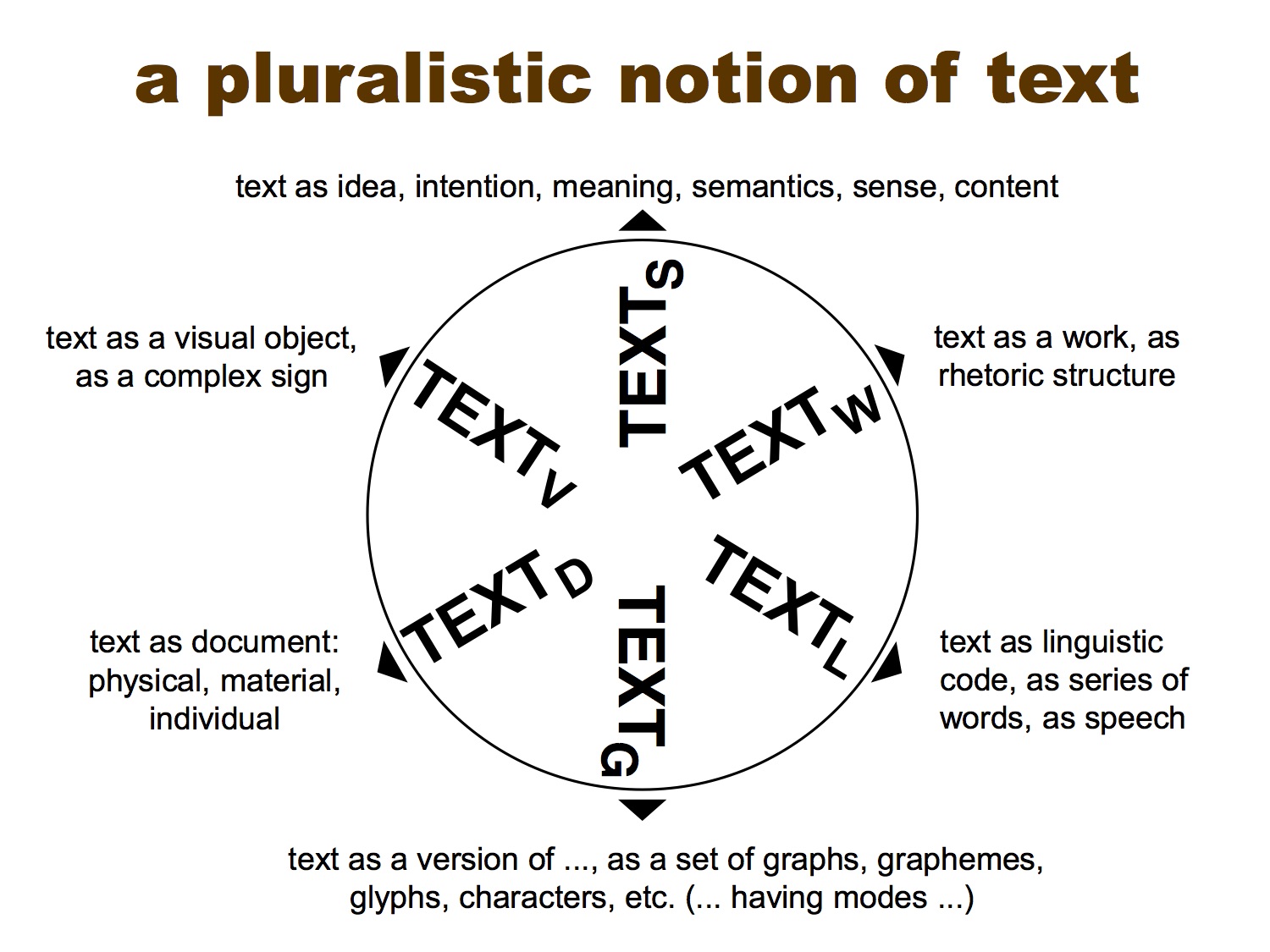

Patrick Sahle’s model (of text modelling):

(For the full slideshow, go to http://dixit.uni-koeln.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Camp1-Patrick_Sahle_-_Digital_Modelling.pdf. And for his essay on the subject, click go to https://www.openbookpublishers.com/htmlreader/978-1-78374-238-7/ch2.xhtml.)

What do you think?

Sahle also provided a useful distinction of the ‘digitised’ versus the ‘digital’ edition. A work that is ‘digitised’ tends to mimic the codex––it is a page by page rendering. This form of digitisation is usually a PDF or even a hypertext marked up in html. But it is not interactive. A digital edition can only fully function in the digital realm––that is, if you have to print a digital edition, the edition would lose its functionality. The digital edition is more interactive

What really distinguishes the two?

Textons versus scriptons: one of the distinguishing features of digital editing. A texton is all of the data that appears in the text file, while a scripton is the text as it appears to the user of the edition (see Pierazzo, Digital Scholarly Editing, p. 34). Put another way, it is raw source data versus the output that users see in the interface.

For example: in a recent documentary editing project on incoming letters to Mark Twain as part of an 1884 April Fools joke, each person is tagged with a pointer to a “personography” (a TEI file listing biographical information):

<text type="letter">

<body>

<pb facs="smith01.jpg" xml:id="pb0001" n="1"/>

<head type="metadata">

<name corresp="#JHS">J. Hyatt Smith</name> to <addressee>

<name corresp="#SLC">Samuel L. Clemens</name>

</addressee>

<date when="1884-03-28">28 March 1884</date> • <name type="place">Brooklyn, N.Y.</name>

<sourceline>(MS: CU-MARK, UCLC 41833)</sourceline>

</head>

The #JHS and #SLC attributes point to @xml:id attributes in a separate personography file:

<person xml:id="JHS">

<persName type="display">Rev. J. Hyatt Smith</persName>

<persName type="full"><surname>Smith</surname>, <forename type="first">John</forename> <forename type="middle">Hyatt</forename></persName>

<birth when="1824">1824</birth>

<death when="1886">1886</death>

<sex>male</sex>

<note><p>Born in Saratoga, N.Y., John Hyatt Smith was educated by his schoolmaster father, then sent to Detroit to work as a clerk. There he was a close friend of Anson Burlingame, who later befriended Clemens in Hawaii. Smith studied for the ministry when he wasn't clerking. After ordination in 1848 he served as a Baptist minister in Poughkeepsie, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Philadelphia before he accepted a position at the Lee Avenue Church in Brooklyn. Smith ran as an independent Republican for a seat in the US House of Representatives and served from 1881 to 1883. In December 1883 he was called by a congregational council presided over by Edward Beecher (brother of Henry Ward Beecher) to fill a temporary pastorship at the East Congregational Church in Brooklyn, where he remained until his death.</p></note>

</person>

The biographical information is also rendered as a network graph.

Clearly these kinds of data could not be printed out, and even if one attempted to print all of the biographical information and the network connections, one would lose the interactivity between texts and individuals and their various connections.

Seminar 5 (Senate House Library): Using TEI for documentary editions: letters and journals

Here is a sample TEI template for a George Bernard Shaw letter in our manuscript collection (The Stirling Collection, Senate House Library):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<?xml-model href="http://www.tei-c.org/release/xml/tei/custom/schema/relaxng/tei_lite.rng" type="application/xml" schematypens="http://relaxng.org/ns/structure/1.0"?>

<?xml-model href="http://www.tei-c.org/release/xml/tei/custom/schema/relaxng/tei_lite.rng" type="application/xml"

schematypens="http://purl.oclc.org/dsdl/schematron"?>

<TEI xmlns="http://www.tei-c.org/ns/1.0">

<teiHeader>

<fileDesc>

<titleStmt>

<title>Letter from G. B. Shaw to William Burton</title>

<author>George Bernard Shaw</author>

<editor>Digital Scholarly Editing Team, London Rare Books School</editor>

</titleStmt>

<publicationStmt>

<p>This is a born-digital diplomatic transcription of an unpublished letter.</p>

</publicationStmt>

<sourceDesc>

<p>Written on one side of a card with Shaw's stock letterhead</p>

</sourceDesc>

</fileDesc>

</teiHeader>

<text>

<body>

<div type="letter">

<opener>

<!-- do we include the pre-printed letterhead? -->

<address><addrLine>[Written sideways in the left margin:] to Mr. <name>William Burton</name>

<lb/>77 Queens Buildings

<lb/>Collinson Street, London SE1</addrLine></address>

<date when="1928-09-23">23<hi rend="superscript">rd</hi>. Sept. 1928</date>

<salute>Dear Sir</salute></opener>

<p>There is nothing in all this that your children will not be able to learn––if they want to––from books by more practiced hands.</p>

<p>I should have guessed you to be a young man with an itch for writing, in which case I should have recommended you to write a thousand words a day for five years to find out whether you could write professionally or not.</p>

<p>It takes as long to make a skilled writer as a skilled carpenter for a man of your turn of mind.</p>

<p>I have only just returned from the continent, where I have passed 2 months out of reach of your <choice>

<abbr>MS.</abbr>

<expan>manuscript</expan>

</choice>

</p>

<closer>

<salute>faithfully,</salute> <signed>

<name>G. Bernard Shaw</name>

</signed>

</closer>

</div>

</body>

</text>

</TEI>

You can also download the XML file by right-clicking here and saving the file (or the link as an xml file on your desktop).

Of course there is plenty more information that you could encode to properly represent this short letter document. What else would you include, and how does it fit into your text model?