Day 1

Monday, 24 June 2019

Today will feature an introduction to the history of scholarly editing, an overview of digital workflow strategies, and an introduction to Markdown and XML.

Aims

-

General grasp of the history of scholarly editing.

-

Facility with transcribing documents in Markdown, HTML, and XML.

Schedule

| Time | Topic | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 12.30 | Registration | |

| 13.00 | Senate House Library Talk | Presentation |

| 14.00 | Seminar 1: Brief history of Scholarly Editing; Digital Editing Workflow | Presentation, Discussion |

| 16.00 | Seminar 2: Transcription and Markup Languages (Markdown, HTML, CSS); Brief Introduction to XML | Digital lab |

Seminar 1: Brief History of Scholarly Editing

Readings

-

Greetham, “A History of Textual Scholarship” (from the Cambridge Companion to Textual Scholarship).

-

A. E. Housman, “The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism” (Art and Error).

-

G. Thomas Tanselle, “The Varieties of Scholarly Editing” (Greetham, 1995).

Lecture notes

Access the slideshow here.

A brief outline of textual scholarship

Peisistratus (560–527 BCE) orders the 'official' text of Homer. The primary challenge was to build a coherent text from myriad versions spoken by the rhapsodes. This could be a viable beginning of textual criticism, i.e., being aware of variance and attending to authenticity and authority (whatever those terms mean).

Lycurgus (c. 390–324 BCE) arranges for single texts of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripedes to be deposited into Athenian archives.

The history of textual editing is a history of arguments about the meaning of terms such as authenticity and authority. It is also a record of humans grappling with the contingencies of cultural imagination, tradition, and artefacts.

What is the textus receptus? When mistakes in a received (published) edition prevail: E.g., Falstaff "babbl'd o' green fields" (Shakespeare, Henry V); "soiled fish of the sea" (Melville, White-Jacket).

284 BCE, Ptolemy Soter founded the Library of Alexandria: manuscript copying was a common practice, since all incoming ships had to declare any manuscripts in their possession. Any manuscripts declared would then be copied and deposited in libraries. Their copies were only labeled differently if they had differences.

The birth of collation as an editorial practice; and dealing with analogy versus anomaly: the Alexandrians sought to emend texts that had, in their judgment, corruptions. Their practice is idealistic: the best text is not based on any actual document but rather a new document that seeks to bring out the best readings from all the extant texts.

Pergamum, the other civic rival to Alexandria, switched to using parchment (animal skin) after Alexandria banished papyrus exports during a trade conflict. Generally, the Pergamanian scholars accepted the necessity of corruption and sought to identify the "best text" based on a careful examination of all surviving witnesses. The "best text" would be based on an actual historical document, rather than the Alexandrian text, which was a reconstructed text. Texts from neither of these epochs survive, but citations of them exist in medieval scholias.

Descriptive Bibliography. Callimachus (c. 305–240 BCE) created the first record of Greek manuscripts, Pinakes (Tablets).

Founding of the Palatine Library in Rome, 28 BCE; establishment of Virgil as the national poet.

Late classical era: the birth of textual commentaries (Servius Honoratus on Virgil, for example). Why is this important? The textual commentaries include quotes of important works and other cultural and historical information that have been otherwise lost. Hugh Cayless offers a good primer on Servius, as well as some thoughts on digital editing, on his blog.

Biblical scholarship: problems of vocalisation, accentuation, and word-division in consonantal Hebrew. Masoretic text (Hebrew and Aramaic copies, c. 7th–9th centuries CE) versus Greek Septuagint translation versus the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Old Testament is far less complicated (textually speaking) than the transmission of the Greek New Testament. New Testament (Greek) features "determined variation" (due to sectarianism in early church). Origen's 3rd-century *Hexapla* presented a parallel text. Jerome's Vulgate, commissioned by Pope Damascus I in the 5th century CE, was the first Latin Bible that was based on surviving witnesses: Greek translations, Hebrew Masoretic texts, Septuagint Greek mss, Origen's text, and Old Latin translations (~8000 manuscripts!).

Medieval period saw a period of conservation, copying mostly religious works and trying to reconcile them, as much as possible, with classical (pagan) works. The Caroline Reformation led to a standardised script that made various European national scripts consistent––a significant portion of surviving manuscripts of classical literature is the result of copies made in monasteries with Carolingian script. Meanwhile, Constantinople's holdings of Greek manuscripts were crucial to Italian humanists' serious return to Greek study in the late fourteenth–early fifteenth century.

Copying work transferred from the hands of monks to those of professional scribes, often in universities. The great poet Petrarch's partial reconstruction of Livy's histories was a rigorous editorial project based on manuscript fragments in many medieval repositories. Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), acting as papal secretary, found manuscripts all over Europe of prominent classical thinkers. Bracciolini even invented a new humanist script that was far more clear and readable than the prevailing textura (i.e., gothic) script of the day. This is a good moment to reflect on the desire for humanists over time to invent inscription technologies that are consistent, readable, and shareable––a set of values very important to so-called "digital humanities" today.

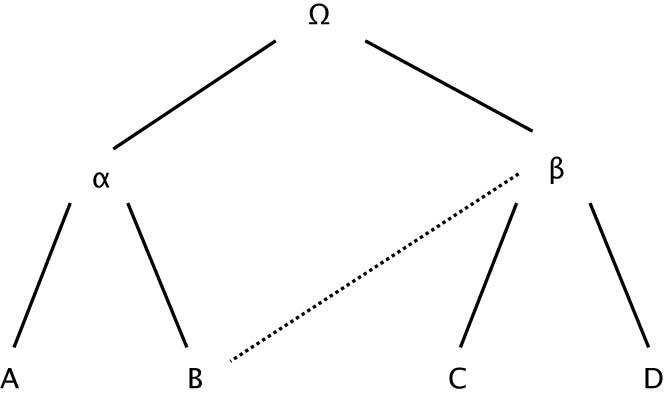

Lorenzo Valla (1407–57), the great debunker of forgeries: the Donation of Constantine and the letters of Seneca and St. Paul, e.g. He also sought to emend Jerome's Vulgate. His edition, based on Greek and patristic texts, was published by Erasmus in 1505. Similarly, Politian (1454–94) searched for earliest recoverable version of a manuscript––this foreshadowed the genealogical method of plotting a linear path of textual transmission. Politian derived the method of eliminatio codicum descriptorum, the removal of "descriptive" or derived copies as witnesses to an authentic version. This led to the method (very much relevant to current practice) of stemma codicum, the "family tree" of textual versions.

- Stemmatics: building a family tree by examining scribal errors in multiple manuscript copies. E.g. Aldine editions. Example of the Erasmus New Testament. As an example:

(Source: https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/4742.1-textual-criticism-as-applied-to-biblical-and-classical-texts)

(Source: https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/4742.1-textual-criticism-as-applied-to-biblical-and-classical-texts)

Philology (OED):

1. Love of learning and literature; the branch of knowledge that deals with the historical, linguistic, interpretative, and critical aspects of literature; literary or classical scholarship. Now chiefly U.S.

3. The branch of knowledge that deals with the structure, historical development, and relationships of languages or language families; the historical study of the phonology and morphology of languages; historical linguistics. See also comparative philology at comparative adj. 1b.

Lachmannian method: identification and evaluation of bibliographic sources with a critical awareness. This comes out of the work of Karl Lachmann (1793–1851), whose 1850 edition of Lucretius claimed that the three extant manuscripts descended from a single archetype. Later witnesses have more errors. Interestingly, Lachmann's Nibelungenlied edition involved more speculation.

Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1753–1824) and his monumental claim that there was no possibility to find or reconstruct the original or best text in biblical texts, because of all of the layers of copying and linguistic shifts (Einleitung in das Alte Testament, 1780–83).

Friedrich August Wolf (1759–1824) similarly argued in his Prolegomena ad Homerum (1795) that it would be impossible to recover Homeric texts.

Housman's thought

Where do science and art meet? "Textual criticism is a science, and, since it comprises recension and emendation, it is also an art."

A matter of reason and common sense, but also not "an exact science at all ... fluid and variable ... neither mystery nor mathematics"... It deals with human frailties---errors.

Editorial problems should be treated as individuals: "must be regarded as possibly unique."

Learning principles from instances: "P]ublic opinion is now aware that textual criticism, however repulsive, is nevertheless indispensable, and editors find that some presence of dealing with the subject is obligatory; and in these circumstances they apply, not thought, but words, to textual criticism. They get rules by rote without grasping the realities of which those rules are merely emblems, and recite them on inappropriate occasions instead of seriously thinking out each problem it arises."

This is to suggest that editors should "look all facts in the face" and avoid sectarianism of thought: "This I cite as a specimen of the things which people may say if they do not think about the meaning of what they are saying, and especially as an example of the danger of dealing in generalisations. The best way to treat such pretentious inanities is to transfer them from the sphere of textual criticism, where the difference between truth and falsehood or between sense and nonsense is little regarded and seldom even perceived, into some sphere where men are obliged to use concrete and sensuous terms, which force them, however reluctantly, to think."

What does he mean by sincerity of a manuscript? "When you call a MS. sincere you instantly engage on its behalf the moral sympathy of the thoughtless ... Our concern is not with the eternal destiny of the scribe, but with the temporal utility of the MS.; and a MS. is useful or the reverse in proportion to the amount of truth which it discloses or conceals, no matter what may be the causes of the disclosure or concealment."

Sincerity and recension; the importance of building. "[E]ven the traditional rules must of course be tested by comparison with the witness of the MSS... if we build structures on our trust we are no critics."

A paradox: "The MSS. are the material upon which we base our rule, and then, when we have got our rule, we turn round upon the MSS. and say that the rule, based upon them, convicts them of error. We are thus working in a circle, that is a fact which there is no denying; but, as Lachmann says, the task of the critic is just this, to tread that circle deftly and warily"

"To be a textual critic requires aptitude for thinking and willingness to think; and though it also requires other things, those things are supplements and cannot be substitutes. Knowledge is good, method is good, but one thing beyond all others is necessary; and that is to have a head, not a pumpkin, on your shoulders and brains, not pudding, in your head."

Editing and history

Interplay between "science" or "scholarship" and "criticism"; the problem of *scientism*.

An act of historical scholarship which requires an answer to this question: "What role do judgment and evaluation play in reconstructing the past?" (Tanselle, 10).

Texts of documents v. text of works.

Is editing historical or ahistorical?

Yuval Noah Harari: history is not the study of the past; it is the study of change.

The role of the editor; the old distinction between lower and higher criticism. Does the reading text matter to interpretation?

Seminar 2: Digital Editing Workflow

Reading

- David Birnbaum, “An even gentler introduction to XML”.

Lecture notes

Digital Editing Workflow and Mental Modeling

If you are interested in creating a digital edition, there are two questions that you must ponder at length before proceeding: 1. What do the documents require? Are you working with manuscripts or print texts (or a mixture of both)? 2. What are your editorial principles? Based on those principle, what is the text model, why are you making it, and what will it be used for? 3. What is the workflow? The answer to (1) will vary quite a bit, depending on your documents, and what kind of edition you would like to produce. We will continue to investigate options to (1) as we move through the course this week. The answer to (2) is a little more straightforward. Since we are concerned with "digital" editing, we need to think in terms of an appropriate computational pipeline.

Basic components of a digital edition

-

Source file(s) of transcribed text and metadata encoded in an open source, machine readable format (Markdown, HTML, XML, JSON). The most thorough, and semantically rich, encoding practice is the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) standards of XML, but it's not necessary.

-

Files that parse (i.e., read) and transform the encoded documents for viewing. Typically these will be XSLT or XQuery or (less common) Python files.

The edition, as transformed by the former, in HTML.

Files for styling the edition's html interface (CSS, JavaScript)

Transcription Options

You must start with a flexible text editor. By flexible I mean an editor that is amenable to Web publishing, and uses non-proprietary open source formatting. Many editors have used proprietary word processors to transcribe their editorial material. While that has some virtues (control of type-setting features, to name one), it presents a lot of problems if you are trying to optimise your workflow. E.g., if you transcribe an edition in Microsoft Word, you would have to transform that document (and all of its attendant proprietary code) into XML or HTML in order to make it work as a digital edition on the Web.

For us, the common understanding is that machine-readable documents in HTML or XML should be our edition files of record. From there, all kinds of transformations are possible, including making printer's copy for a book. Ideally, all documents would be transcribed in TEI XML from the beginning, but for a variety of reasons that is not always practicable.

First we will look at the most basic of transcription methods: Markdown. This is lightweight web authoring at its best.

Markdown exercise

- Access the Markdown slides here.

- Copy Tennyson’s “Early Spring” here.

- Access the web-based Markdown editor, Dillinger.

- Using Markdown syntax, mark up the following in the Markdown editor on the left side of the interface (click here for the Markdown cheatsheet):

- a main header (for the title), and italicise it;

- a secondary header (for the author);

- a hyperlink from the author’s name to a web page (say, Poetry Foundation or Wikipedia) with his biography;

- consider what information would be useful to the reader;

- create a contextual note for one of the lines (possibly the “Source”?), or write a contextual headnote.

Once your markdown document is complete, explore the preview and export options (Preview As, Export As). Your document will now be available in as many file formats as are available. You can navigate to the file yourself and open it in your browser.

Finally, right click on your HTML file, and click “Inspect.” Have a look at the way your Markdown was rendered into HTML and CSS.

How do you get from markdown to xml? Two good options are Pandoc and OxGarage. I prefer using Pandoc for my transformations (my favourite probably being the markdown > PDF transformation). OxGarage is also good, and a little bit simpler to use: it can convert several types of documents into TEI-XML.

The other option is to open a new TEI-XML document in oXygen or your preferred text editor and simply copy-and-paste the body of the html file into the <body> element of the xml file.

Brief Introduction to XML

Exercise

Apply XML tags to the Tennyson poem. Think about description: what kinds of information about the text would you like to tag?